Ever wondered what were the most famous ancient Greek battles? I’ve put together a list of the most important ancient Greek Battles, all sorted in chronological order.

The selected battles from this list were chosen because of their impact not only on the balance of power in Ancient Greece but also because of how they affected the course of history in other regions as well.

Maybe you will ask? But what are the top battles that defined Ancient Greece in order of importance?

I will answer you by selecting only 6 famous Greek Battles from this list and making a short-tier list. Sharing first place are the Battles of Marathon and Thermopylae. On the second place of the tier list would be the Battles of Platea and Mycale.

The third, but not less important place would be the Battles of Issus and Gaugamela.

You may wonder, why I choose this order on this tier list.

Simple, because these 6 battles are part of a larger and far more complex historical process.

The Battles of Marathon and Thermopylae saved the Ancient Greek World, the Battles of Platea and Mycale allowed the Greeks to start their revenge against the Persians.

With the victories at Issus and Gaugamela, Alexander the Great successfully completes the process started by King Leonidas and Themistocles.

See below the entire list of famous Ancient Greek Battles and the interesting stories behind them.

I. Battle of Marathon (490 BC)

Opposing forces: Athenians vs Persians

Athenians

Commanders: Miltiades, Callimachus, and the other strategos.

Estimated strength: between 10.000-11.000 troops.

Persians

Commanders: Arthapernes, Datis, and Hippias

Estimated strength: 600 triremes, ancient sources give exaggerated figures between 200.000 to 600.000 troops.

Modern sources agree on an estimated force of between 25-50.000 soldiers(infantry, archers, and cavalry).

Causes:

– the rebellion of the Ionian Cities against the Persian rule

-Athenian support for the Ionian revolt against the Persian rule in Asia Minor.

-Darius desire to take revenge on Athens for supporting the rebellion.

Summary:

Probably the Battle of Marathon is wrongfully presented by many historians as a battle between East vs West, but this clash between Athens and Persia did really save something important.

More exactly the Athenian victory at Marathon saved the young and fragile Athenian democracy from complete annihilation.

If the Persians have won, the immediate result would’ve been the rise to power in Athens of a Puppet Regime, under Persian control, most likely under the former tyrant Hippias.

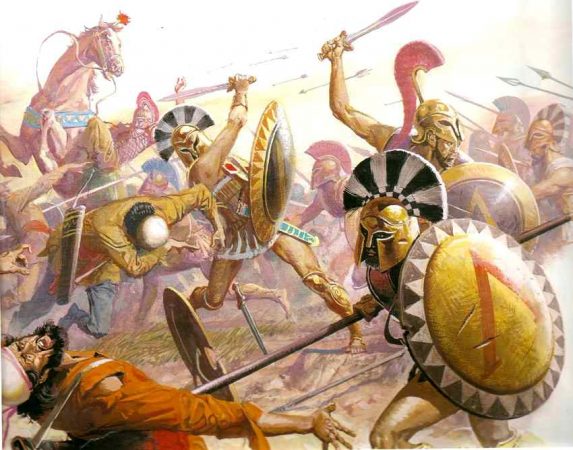

Under the leadership of Miltiades the Younger, the Athenians successfully repel the Persian invasion with the help of a bold strategy.

On the day of the battle, the Athenian army flanks were reinforced, while the center was somehow weakened.

Before reaching the Persian camp, Miltiades orders the Athenian hoplites to quickly charge the Persian lines, so that the enemies could not have enough time to deploy their deadly archers and cavalry.

The result was a crushing defeat for the Persian forces led by commander Artaphernes.

During the battle, only 192 Greek troops would lose their lives, while the Persian casualties were much greater, around 6.400 soldiers according to Herodotus.

The Battle of Marathon marks the failure of Darius’ invasion of Greece. The young Athenian democracy was saved and together with it, the entire Greek civilization.

Consequences:

-failure of Darius I’s punitive expedition

-failure of Hippias to retake the Athens

-the salvation of the young and fragile Athenian democracy

-first major Persian defeat in Europe

II. Battle of Thermopylae (480 BC)

Opposing forces: Greek city-states coalition vs Persians

Greek city-states

Commanders: King Leonidas of Sparta, Demophilus of Thespiae, Leontiades

Estimated strength: in the initial phase of the battle around 7000 troops.

In the final phase of the battle: 300 Spartans, 400 Thebans and 700 Thespians

Persians

Commanders: Xerxes I, Mardonius, Hydarnes II, Artapanus

Estimated strength: ancient sources give exaggerated figures, Herodotus even speaks about 2.5 million troops, which would’ve been logistically impossible.

Modern historians agree on figures between 120-300.000 soldiers.

Summary

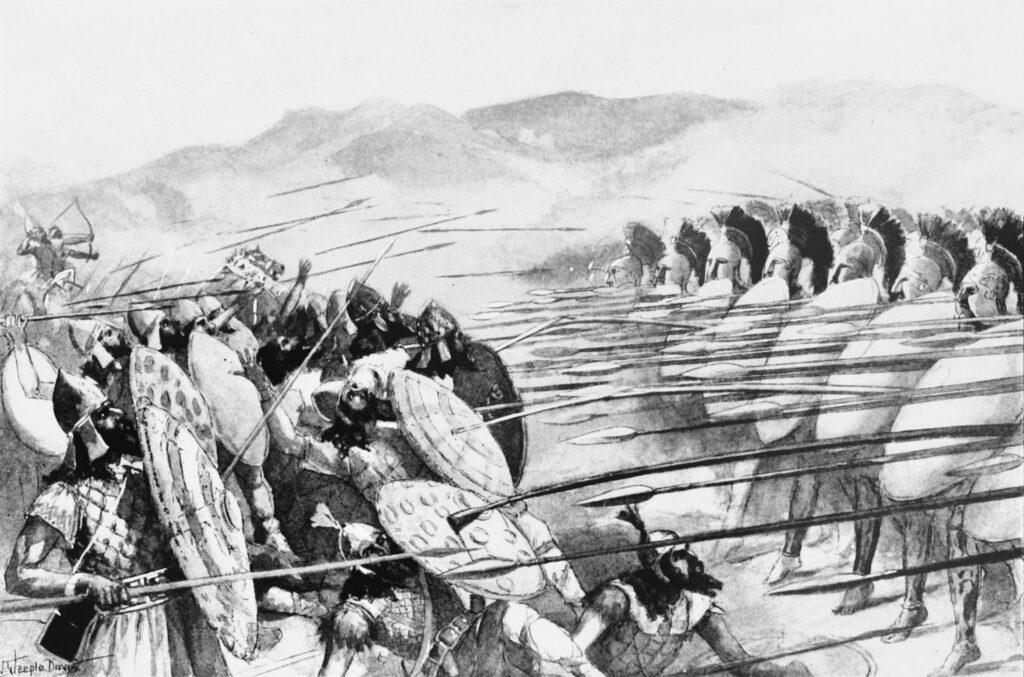

Under the leadership of King Xerxes, the Persian army starts a new massive campaign against Greece in 480 BC. Their main objectives were the cities of Athens and Sparta and of course to subdue the entire Greek mainland.

Faced with this threat, the Greeks city-states rally and agree to create a United Coalition to face the Persian threat.

The leader of this coalition would be Sparta, because of their famed warriors and reputation as invincible in land battles.

Together with an army of around 6000 Athenian soldiers, 700 Thebans, and 400 Thespians, they marched to the mountain pass of Thermopylae and prepared their defensive positions.

The location of the Battle was strategically chosen by both the Spartans and their Greek allies.

The narrow pass, perfectly for a defensive battle, denied the Persians their numerical advantage, while also keeping the Greek losses at a minimum.

The terrain also helped the defenders because it prevented any major cavalry flanking maneuvers from the enemy.

The only downside of the location was represented by a mountain pass, parallel with the Thermopylae pass.

If discovered, it would mean the end of the Greek resistance.

Leonidas knew very well about this pass and stationed there a small Phocian unit to delay any possible advance from the Persians.

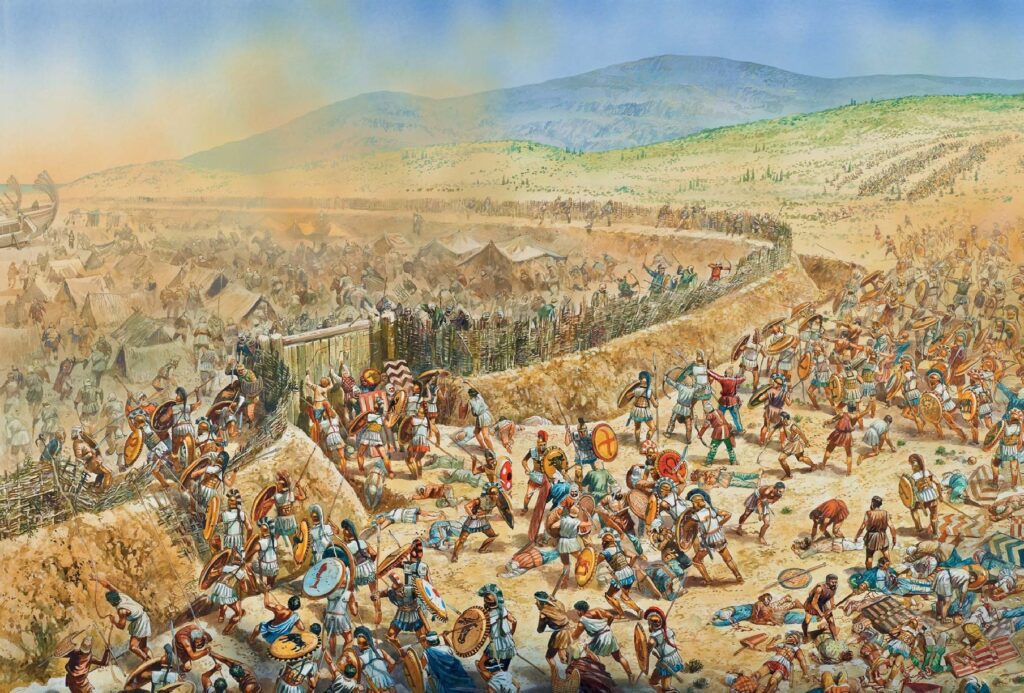

We all know the next chain of events, the Spartans along with their allies(yeah they were not alone like the movie 300 wants us to believe) stood their ground and the Persians suffered heavy losses.

If that mountain pass was not discovered, it is likely that the outcome of the Battle could’ve been different.

The mountain pass was discovered due to treachery/betrayal by a Greek, by the name of Ephialtes.

He showed the path to the Persians.

The small Phocian garrison who guarded the secret mountain pass was quickly overrun and it became clear that the defensive position at Thermopylae was compromised.

Leonidas realizes that the end is near. The Spartan King give orders to the other Allied troops to fall back, while he with his Spartans will delay the Persian advance as much as possible.

This decision, though noble because it saved the lives of thousands of people, also meant certain death for Leonidas and his men.

Unlike the events presented in the famous movie, along with the 300 Spartans, 700 Thespians and 400 Thebans will also lose their lives.

Leonidas’ sacrifice was not in vain.

The fierce resistance and the heroic sacrifice of the Spartans and their allies at Thermopylae saved the Greek world because it offered the Greeks a precious resource: time.

Time for organizing another resistance against Xerxes.

Time for Athens to consolidate her fleet.

Time for Sparta and their Peloponnesian allies to fortify the Isthmus of Corinth.

How many of these would’ve been possible if the Persian army would’ve gone through Thermopylae without any resistance?

Even if they lost the battle, Leonidas and the Spartans’ sacrifice secured them a rare but special place in history.

Consequences:

-a minor setback for the Persian advance into Greece

-looting and pillaging of Athens

-it bought precious time for the free Greek city-states to regroup

-through their exemplary heroism and sacrifice Leonidas and the Spartans provided a morale boost for the other Greek fighters

III.Battle of Salamis(480 BC)

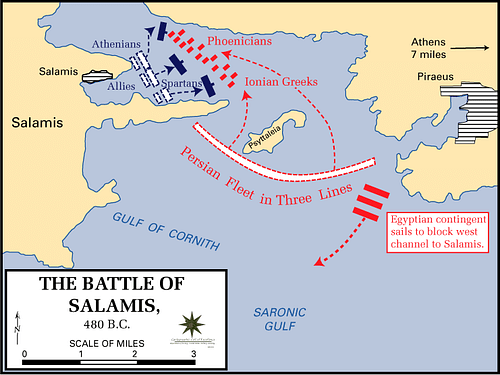

Opposing forces: Greek coalition fleet vs Persian fleet

Greek coalition

Commanders: Themistocles and Eurybiades

Estimated strength: around 370 ships.

Persians:

Commanders: Xerxes, Tetramnestos, Damasithymus, Ariabignes, Achaemenes, Artemisia I of Caria

Estimated strength: ancient sources tend to agree that the Persian fleet was superior numerically to the Greek fleet, most probably between 600-1200 ships.

If Marathon put an end to Darius’ plans of punishing Athens, the naval Battle of Salamis represents the end of Xerxes’ (Darius’ son) ambitions of total conquest of the Greek city-states.

With the heroic sacrifice of the Spartan defenders at Thermopylae, the Persian advance was delayed by almost 1 week.

This in turn gave the Greek coalition forces time to reorganize their navy near Salamis and the ground defenses around the Isthmus of Corinth.

With the fall and sacking of Athens, the only region of mainland Greece which was not fully conquered by the Persians was the Peloponnese peninsula.

A clever Athenian strategos, Themistocles, convinced the Greeks that for the defense of the Peloponnese peninsula against naval raids by the Persians, this threat had to be dealt with as soon as possible.

Themistocles’ plan was simple and very bold, to lure the mighty Persian fleet into a trap and destroy it.

Fortunately for the Greeks, the Persians took the bait.

Thinking that the Greek fleet was about to retreat from the Island of Salamis, Xerxes sent his massive fleet in an attempt to block the Greeks.

The strategy of the Persian leader would soon backfire and as a result around 200-300 Persian ships were lost, while the Greek fleet casualties were minimal.

With the victory at the naval Battle of Salamis, the Peloponnese Peninsula was saved from Persian naval raids and the Greeks had the necessary resources to focus on the future ground battles against Mardonius forces.

Consequences:

-the destruction of the Persian fleet

-the Peloponnese Peninsula was saved from Persian naval raids

-Xerxes decides to retreat with the bulk of his army

-the Athenians are able to regroup and retake the city of Athens

-the Spartans successfully fortify the Isthmus of Corinth.

IV. Battle of Himera (480 BC)

Opposing forces: Syracusans vs Carthaginians

Greeks

Commanders: Gelo and Theron

Estimated strength: likely 50.000-55.000 total troops(infantry and cavalary)

Carthaginians

Commanders: Hamilcar the Magonid

Estimated strength: modern historians agree on 50.000 troops, ancient sources give unrealistic figures of around 300.000 soldiers.

Causes:

-deposition of the pro-Carthaginian ruler of Himera in 483 BC.

-Carthage’s attempt to restore the deposed tyrant of the Sicilian city of Himera.

-Theron and Gelo alliance to prevent the spread of Carthaginian influence

Summary

In the same year of the crucial battles of Thermopylae and Salamis, when the Greeks saved their freedom from the Persian rule; the Greeks in Sicily, led by 2 tyrants: Gelo and Theron, successfully defended their independence against a major threat represented by huge Carthaginian invasion.

Because of the Battle of Himera(480 BC), some modern historians speak about the existence of a Persian-Punic plot to destroy the Greek world.

This theory is mostly based on the assumption that the battles of Salamis, Thermopylae, and Himera took place in the same year.

However, there is no evidence of a link, alliance, or secret negotiations between the Persians and the Carthaginians to simultaneously destroy the Greek world.

The Battle of Himera as it became known in history, has a very intricate background.

Two centuries before 480 BC, Sicily was divided between the Greeks and the Carthaginians and it appeared for a while, that peaceful coexistence could be possible.

With the rise of tyranny in the Greek-controlled area of the island, peace was not an option.

In 483 BC, one crucial city, Himera would depose its Carthaginian ruler. The political unrest in the city was quickly exploited by Theron, a tyrant of another Sicilian town, Acragas.

Terilus, the deposed ruler of Himera, asked Hamilcar Magonid, the ruler of Carthage to intervene in this dispute with a massive invasion force.

Three years passed until Hamilcar was able to gather a significant military force to deal with the Greek threat.

In 480 BC, the Carthaginian navy sets sail.

Herodotus like in many other stories, gives a very exaggerated figure, a 300.000 strong Carthaginian army.

The forces of the Greek tyrants, Gelo and Theron were at best composed of 50.000 infantry troops and 5.000 cavalry units.

The Carthaginian expeditionary force landed near the city of Himera and set up 2 camps, one camp would be near the sea with the purpose of guarding the fleet.

The other camp was facing the city of Himera itself.

Initially, Theron attempts to sally out the city and repel the Carthaginian army, but the Greek assault backfires.

Without any other options left, Theron sends a message to his most important ally, Gelo, a tyrant of Syracuse, the most prosperous city on the island.

Gelo doesn’t waste time and arrives with his army near Himera to deal with the Carthaginian threat.

His initial success is represented by the capturing or killing of the Carthaginian foragers, which complicates logistical issues for the invaders.

Now comes, the most interesting part of this battle.

Lacking cavalry support because of the storm, Hamilcar requests cavalry reinforcements from the nearby Carthaginian colonies.

What happens next looks like an episode from the Trojan war.

The Greeks intercepted the Carthaginian messenger on his way and learn this way about Hamilcar’s plans.

The Greeks came up with an ingenious plan, they would disguise their cavalry and pretend that they are the reinforcements.

The Carthaginians from the Sea camp had swallowed the bait. At the right moment, the Greeks infiltrated in the camp assassinated Hamilcar and burned the Carthaginian ships, tents, and other defensive works.

While the Greeks were successful in the Sea Camp against the Carthaginians, at the Punic camp near the city, the battle was still not decided.

The Carthaginians and the Greeks led by Gelo fought hard around the hill.

When the news of the success of the Sea Camp arrived, the Greeks finally gain the upper hand.

The Carthaginians retreated into their camp where another fierce battle took place.

The Greeks lost the military initiative because instead of finishing the fighting, they started to loot the enemy tents.

The Iberian infantry of the Carthaginians took advantage of Greek disorganization and manages to achieve some minor military gains.

At this critical moment of the battle, Theron with his forces, sally again from the city of Himera and joins his forces with Gelo’s army on the hill.

The arrival of Theron’s army represents the final blow and the nail in the coffin of the Carthaginian invasion of Sicily.

Consequences:

The biggest consequence of this battle is represented by the major loss of both power and resources by Carthage.

From now on, Carthage could no longer hope to conquer the entire island of Sicily. In the long term, the battle of Himera forced the Carthaginians to look for other lands to conquer: Spain, and Africa.

Despite the fact that the Carthaginians were so decisively defeated, the peace treaty conditions were not harsh.

Carthage was only forced to pay 2000 talents as war reparations and didn’t lose any territories.

On the other hand, the Greeks were not able to exploit this victory because the political landscape in Sicily was very divided.

Fighting among local tyrants would continue and prevent any further expansion of the Greek influence in Sicily.

V. Battle of Plataea(479 BC)

Opposing forces: A coalition of Greek-city states vs Persians

Greek coalition

Commanders: Pausanias, Amompharetus, Arimnestos, Aristides

Estimated strength: between 100.000 to 110.000 troops according to historians Herodotus, Diodorus, and Trogus.

Persians:

Commanders: Mardonius, Artabazos, Masistius

Estimated strength: between 300.000 to 500.000 troops according to Herodotus and Diodorus of Siculus.

Modern historians agree that between 70.000 to 120.000 troops are more plausible numbers.

The last decisive land battle of the Greco-Persian wars. The Battle of Plataea is often overlooked and many historians didn’t treat it with the same importance as the Battles of Salamis and Thermopylae.

After the unlikely, yet decisive naval victory of the Greeks at Salamis, Xerxes realizes that his plans for quickly conquering the Greeks have been shattered.

As a result, the Peloponnese peninsula has been saved and Xerxes decides to retreat with most of his army, leaving only a significant force under the command of General Mardonius.

Mardonius wasn’t able to change the tide of the war in Greece and decides to set camp in Boeotia in 479 and regroup.

A coalition of the free Greek city-states( Sparta, Athens, Corinth, Megara, and many others) assembles a huge army by the standards of the time and marches directly against the Persians.

Knowing that the Persians had the advantage in cavalry force, the Greek commanders decided that it is best to hold the high ground around the Persian camp and wait for the decisive opportunity to strike.

The result was a stalemate between the 2 opposing forces for 11 days.

According to some ancient Greek historians, Mardonius tries to use intrigue and manipulation in an attempt to break the unity of the Greek army, without success.

Failing to break the Greek coalition, Mardonius tries to lure the Greek army into the open field, where he knows that the Persian cavalry had the advantage.

Unfortunately for the Persian commander, the Greeks hold their ground and even killed the leader of the Persian cavalry, the Persian maneuver failed.

The Greeks, knowing that the Persian cavalry was no longer a threat, marched on the main camp and finished the remaining pockets of Persian resistance.

According to Herodotus, 257.000 Persians died during the Battle of Platea. Of course, this figure is hard to believe.

Another historian, Diodorus, mentions that the Persians only lost 100.000 troops.

The Greek losses were even lower, Herodotus speaks only about 159 soldiers, while Ephorus and Diodorus only has about 10.000 losses.

The Battle of Platea meant the end of the last Persian plan to dominate mainland Greece.

It marked the beginning of a new historical phase in the relations between the Greeks and the Persians.

From now on, the Greeks will be the ones who will attempt to take the offensive to the Persian lands.

Consequences:

-the annihilation of the Persian army led by Mardonius

-Persian threat over mainland Greece ceased to exist

-it boosted the morale of the Greek fighters before another decisive fight, the Battle of Mycale.

VI. Battle of Mycale (479 BC)

Opposing forces: a broad coalition of Spartan, Athenian and Corinthian troops vs the Persian fleet and army.

Greek coalition

Commanders: Leotychidas II; Xanthippus; Perilaus

Estimated strength: between 120-250 ships and 40.000 troops

Persians

Commanders: Artayntes; Ithamitres; Mardontes; Tigranes

Estimated strength: around 300 ships and 60.000 troops.

Causes:

-Greek naval victory at Salamis allowed the Greek forces to move on the offensive

-Xerxes retreats from Greece with the bulk of the Persian army

Summary.

The naval victory of the Greeks at Salamis allowed them to move freely on the sea and prepare for a large-scale offensive battle against the remains of the Persian fleet.

The combined Spartan, Athenian and Corinthian forces were also encouraged by the arrival of emissaries from the Ionian cities in Asia Minor with promises that they would rise against the Persians if they manage to cripple the Persian fleet.

In 479 BC, the Greek fleet arrives near Samos(modern-day Turkey), where the remnants of the Persian fleet were located.

The cowardly Persians, knowing that they didn’t stand a chance at sea against the Greeks, choose to fortify their positions on land around mount Mycale with materials from their fleet.

Their fortification works and defenses were also aided by another local Persian army.

The strength of the Greek force is estimated at around 40.000 troops while the Persians had numerical superiority with over 60.000 troops.

The Greek historian Herodotus doesn’t mention the exact casualties during this battle from either side, but we could imagine that the battle was fierce so as a consequence the casualties on both sides were significant.

After the victory, the Persian fleet was burned by the victorious Greek coalition.

The 2 battles that ended the Greco-Persian war: Platea and Micale are significant because the victory of the United Greek coalition over the Persians completely removed the Persian threat, at least for a while.

The same battles were also the beginning of a new phase in the Greco-Persian wars. It marked the beginning of the Greek revenge/counterattack.

Consequences

-the destruction of the remnants of the Persian fleet

-along the contemporary Battle of Platea, it represents a turning point in the Greco-Persian wars.

-the liberation of the Ionian cities.

-the foundation of the Delian League under the hegemony of Athens

VII. Battle of Pylos(425 BC)

Opposing forces: Athenians vs Spartans

Athenians:

Commanders: Demosthenes

Estimated strength: around 600 troops(hoplites and light infantry)

Spartans:

Commanders: Thrasymelidas and Brasidas

Estimated strength: not exactly known, most probably outnumbered the Athenians.

Causes

Athens’s strategy of weakening the Spartans through naval raids along their shores in the Peloponnesian Peninsula

Summary

If you ever thought that Spartan hoplites never surrender, then the Battles of Pylos and Sphacteria will prove that you are wrong.

These 2 battles have proven that the Spartan hoplites did know how to surrender when the odds were totally against them.

Until the Battle of Pylos, Athens used its mighty fleet only to harass the vulnerable Spartan settlements in Peloponnese.

Thanks to the vision of the Athenian commander Demosthenes(the occupation of Pylos was not planned by Athens itself) the Athenians will take the raiding in Peloponnese to the next level.

Demosthenes’ plan was bold and at the same time ingenious. The Athenian leader planned to occupy the harbor of Pylos, located in the South-Western part of the Peloponnesian Peninsula, and use it as a base for further raids against inland Spartan settlements.

In the long term, the plan was to incite helot revolts, and Pylos would be used as a base for equipping these rebels.

At first, the Spartans thought that this was again an ordinary Athenian raid and that the enemy will leave soon their positions.

When they realized the true intentions of the Athenians, the Spartans were so shocked, that even King Agis interrupted his invasion of Attica and quickly returned to Sparta with his army so he can deal with the new threat.

As anticipated by Demosthenes, the Spartan’s plan was to attack the Athenian fortifications from both land and sea.

Demosthenes know very well that he couldn’t defeat alone the enemy forces, so he sent 2 Athenian ships to ask for reinforcements from the Athenian fleet located in Zacynthus.

Upon hearing the news, the 50 ships of the Athenian fleet from Zacynthus had set sail to help the garrison from Pylos.

Until their arrival, Demosthenes was faced with the almost impossible task of holding against the Spartan assault.

The Spartans moved in, and occupied the island of Sphacteria which guarded the entrance of the harbor of Pylos.

At the same time, the Spartan navy blockaded the Port of Pylos.

The Spartan army attempted to storm the Athenian positions but was repulsed and forced instead to lay siege to the Athenian garrison. The failure of assaulting the Athenian positions would prove to be a great mistake for the Spartans.

Remember the 50 Athenian ships? Well, they arrived just in time to turn the tide of the battle, not only that they lifted and crushed the Spartan naval blockade, but now the Spartan garrison on the island of Sphacteria was completely cut-off from the rest of the world.

The hunter became the hunted.

The news that 440 Spartan hoplites, many of them being homoioi(Spartiates) had sent a shock wave to the Spartan government who sent envoys in an attempt to negotiate a favorable end for this situation.

You may wonder, why bother with 440 soldiers? It is important to note that at the high of its power, the Spartan army could field in the best-case scenario at least 10.000 troops.

So nearly 500 troops lost, representing at least 5% of the total strength of the Spartans, was not something they could afford.

The Athenians knowing the importance, first attempted to use the trapped Spartan garrison as a bargaining tool and obtain from the Spartan government an agreement as favorable as possible.

Unfortunately, the negotiations didn’t reach an end with an agreement and hostilities resumed, leading to the second phase, the Battle of Sphacteria.

Consequences:

-Athens gain the upper hand in the war

-an important number of Spartan citizens are trapped on the island of Sphacteria

-the Spartans lost the military initiative

-the Athenians have establish a land base in the Peloponnese Peninsula from which they could threaten the Spartans directly.

VIII. Battle of Sphacteria(425 BC)

Opposing forces: Athenians vs Spartans

Athenians

Commanders: Demosthenes and Cleon

Estimated strength: around 11.000 troops( hoplites and light troops together)

Spartans:

Commanders: Epitadas, Hippagretas and Styphon

Estimated strength: 440 hoplites

Causes:

-Athens’s ambition to wage war on Spartan soil by undermining the helot system.

-Spartan attempt to destroy the Athenian fortified outpost at Pylos

The battle of Sphakteria (425 BC) is the second stage of the battle that ended with the surrender of the Spartan army.

After failed negotiations, the fight between Athens and Sparta over Sphakteria resumes. The Spartans continued their attacks against the Athenians at Pylos, while the Athenians maintained a naval blockade of Sphacteria. While both sides were under siege, the Spartans made efforts to transport supplies to their troops.

Volunteers were called to attempt to transport supplies to the island, for a fee and freedom as a reward for the helots. Some waited for the right weather and then sailed to the island at speed, destroying the ships but gaining the reward. Others swam underwater, carrying items protected by skins.

As the siege dragged on the Athenians worried that the Spartans would escape.

This prompted Cleon, who had been instrumental in rejecting the Spartan peace offer, to become angry.

In an attempt to restore his popularity he tries to blame general Nicias, son of Nikiratos, for his failures, arguing that a real leader would have already taken over the island. This had the consequence of causing the municipality to reflect that: ” since the army was not capable of carrying out something so simple, why did Cleon not take the lead himself in order to prevail in the siege.

Nicias perceiving the maneuver gave him permission to assemble the required army and take command of the siege. Finally, Cleon being bound, had no choice but to go to Sphakteria. He takes up the stake and announces that he will take the island in twenty days, without requiring additional Athenian troops.

Cleon perfectly times his arrival at Sphakteria. Demosthenes was reluctant to risk a landing on the island because it was covered with dense forest and paths and he believed that this gave the Spartans a great advantage. But shortly before that, Cleon accidentally causes a fire in the forest and most of the trees burn. The fire revealed a number of possible disembarkation points, as well as that there were more Spartans on the island than previously thought.

The two Athenian generals send a messenger to ask the Spartans if they wish to surrender on generous terms. When the offer is rejected, they wait a day and then launch a surprise attack on the island. The Spartans were divided into three camps. The main camp, under Epitadas, was in the center of the island, flat and the best watered due to the presence of a spring (an important factor for survival). In addition, there was a garrison of thirty men-at-arms at the end of the island which the Athenians chose to attack (probably the southern end), and another small detachment stationed at the opposite end, opposite the promontory of Pylos. This was the rockiest end of the island on which there was an old fortress that the Spartans intended to use as a shelter.

The Athenians put 800 hoplites on board the ships while it is still dark. The ships then sail out to sea, as if they were going to carry out their usual daily patrols, but eventually land on the island. The Spartans are taken by surprise. This allowed Demosthenes to bring the rest of the army, namely the allied forces and the crews of the seventy Athenian warships (800 archers and at least 800 peltasts). This army is then divided into groups of about 200 men and these are deployed on high points around the main Spartan position. The Spartans are trapped. If they attempted to attack any part of the Athenian force, they would themselves be exposed to attacks from the rear, while the lighter-armed Athenians would be able to retreat.

When Epitadas realized that the Athenians had landed on the island, he marshaled his men and moved to attack the Athenian hoplites, anticipating a typical hoplite skirmish.

Eventually, the Spartans found themselves being flanked by archers, peltasts, and slingers. The Athenian hoplites meanwhile do not advance, as a result of which the Spartans, unable to approach their objective, retreated and fortified themselves in the fortress. The Athenians followed and launched a direct attack, but this time the advantage was with the Spartans and so they failed to push them from the fort.

The solution to the problem was given by the commander of the Messinian military division. After asking Cleon and Demosthenes to give him some archers and light troops he made his way around the rocky coast of the island until he reached a hill behind the fortress. When the troops appeared behind them the Spartans abandoned their outer lines and fell back.

At this point, Cleon and Demosthenes called for a halt to the battle and sent a herald once more to offer terms of surrender. The Spartans meanwhile had lost Epitadas, who had been killed, while the second in command, Hippagretas , was badly wounded. These events made the third in line, Styphon , the leader. According to Thucydides most of the Spartans when they heard the heralds lowered their shields and made it clear that they wanted to surrender, so Styphon had no choice but to begin surrender negotiations.

After consulting with Spartan officials on the mainland (who told him “the decision is yours, as long as you don’t do anything dishonorable») Styphon decided to surrender.

The Athenians had won a valuable prize. Of the 440 hoplites who were trapped on the island, 292 were captured and taken to Athens. Of these, 120 were ” similar .””, quite a large percentage for such a small group. The surrender of the Spartans shocked the entire Greek world, as they were not expected to surrender, but to fight to the death, regardless of the odds of victory or defeat.

The surrender also caused great dismay in Sparta and triggered a series of “peace offers”. The prisoners were an important factor when, four years later, the “Nicaean” peace (421 BC) stopped the war for a short time, as one of the clauses of the peace treaty stipulated that all Spartans be imprisoned in Athens or in any Athenian territory.

IX. Battle of Delium(424 BC)

Opposing forces: Athenians vs Boeotians

Athenians

Commanders: Hippocrates

Estimated strength: around 17.000 troops(hoplites and light infantry)

Boeotians

Commanders: Pagondas

Estimated strength: 18.500 in total(hoplies, light infantry, cavalary and peltasts)

Causes:

Athens’s ambition to knock off the Boeotian League(the biggest allies of Sparta) out of the Peloponnesian War.

Summary

After the victories against the Spartans at Pylos and Spachteria, it appears that Athens gained the upper hand in the war. Instead of pursuing the raids against the Spartans, the Athenians suddenly shifted their attention against the Beotian League, the most important ally of Sparta outside the Peloponnese Peninsula.

The Athenians came up with a very elaborate plan to knock the Beotian League out of the war.

Pro-democratic factions inside the city-states would rise against the oligarchic regimes in Beotia and attempt to overthrow them.

In perfect synchronization with the popular unrest, 2 Athenian armies will attack Beotia from 2 directions and attempt to crush the forces of the Beotian League.

The ultimate goal was to establish pro-Athenian regimes in the cities of Beotia.

On paper, the Athenian plan looked perfect. So what went wrong?

First, Spartan spies learned about the plan and informed their Beotian allies.

The oligarchic regimes didn’t waste time and harassed the internal opposition before they had any chance to organize the riots.

The Athenian 2 prong-attack also failed. One of the Athenian generals decides to retreat.

First of all, Demosthenes who was in charge of leading the attack from Siphae, arrived too early and instead of pursuing the attack, decided to retreat.

This decision meant, that the Theban army under the leadership of Pagondas was free to concentrate against the Athenian army led by Hippocrates.

Hippocrates led his army into Beotia and establishes a fortified base around the Temple of Apollo near the village of Delium.

Soon, the Beotian army joins the battlefield. Initially, the Beotarchs were reluctant in engaging the Athenians in a decisive battle.

After Pagondas motivational speech, the decision of the Beotarchs quickly changes.

For defeating the Athenians, Pagondas a brilliant military leader, uses for the first time an ingenious infantry tactic, one which will prove to be decisive.

His right flank, consisting of the best hoplite troops, was heavily reinforced. Instead of the 8-row deep hoplite formations, Pagondas increased the size to 25 rows, providing this way an advantage over the Athenian left flank.

The strategy was a risky one because the center and right flank of the Theban army were much weaker.

Pagondas gamble ultimately proves to be the winning move. On the day of the battle, the Athenian flanks were routed, and over 1.200 Athenian soldiers lost their lives.

With the threat of the Athenian army now over, Pagondas and his army marched against the Athenian fortifications near the temple of Apollo and lay siege to them.

According to Thucydides, the Beotians even improvised an ancient flamethrower and burned the wooden fortifications.

The Athenian plan to knock out the Beotian League out of the war proves to be a costly mistake, and it will not be the only one for them.

Consequences:

-Rise to regional power status of the Boeotian League

-Failure of Athens to gain the upper hand in the Peloponnesian War

-Major turning point in the Peloponnesian War

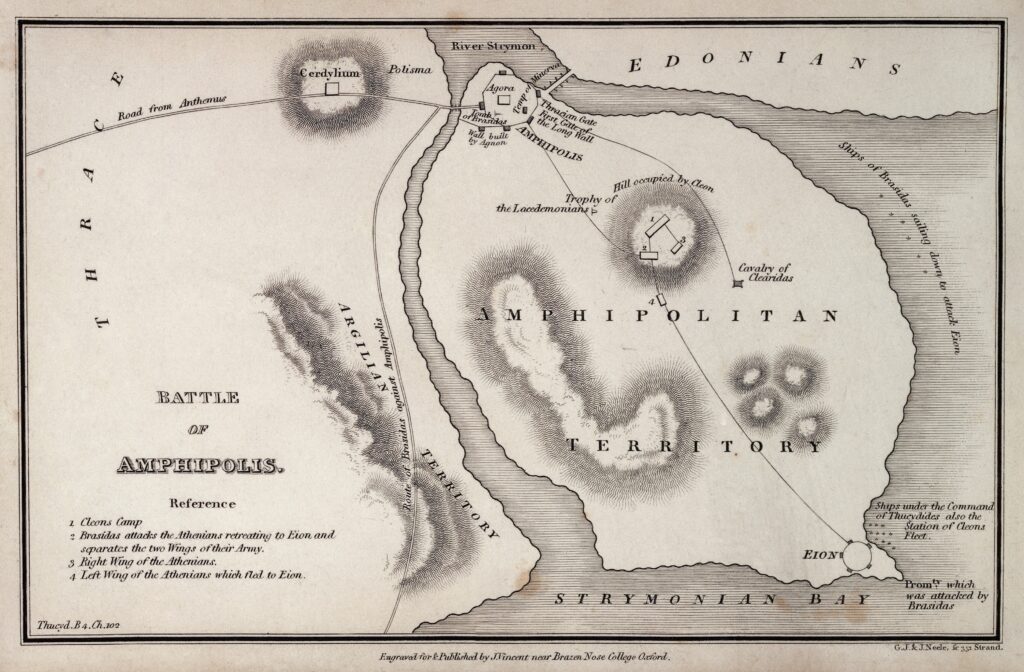

X. Siege of Amphipolis(422 BC)

Opposing forces: Athens vs Spartans

Athenians:

Commanders: Eucles, Thucydides, Cleon

Estimated strength: around 2000 troops

Spartans

Commanders: Brasidas and Clearidas

Estimated strength: around 2.500 troops

Causes:

Brasidas’ expedition to capture the Greek city-states of the Delian League from Northern Greece.

Athens attempt to recapture the vital city of Amphipolis.

After the major turning point represented by the Athenian defeat at the Battle of Delium, it was now Sparta’s s time to strike back.

While Athens was busy with their plans of knocking the Beotian League out of the war, the brilliant Spartan commander, Brasidas, assembled a force and marched to Northern Grece.

In the summer of 424 B.C, Brasidas army linked up with the forces of the Macedonian King Perdicas II.

Afterward, Brasidas campaign in Northern Greece started with the conquest of the colony of Acanthus, and in early December 424 BC, Brasidas forces were close to the main objective: Amphipolis.

Amphipolis was defended by a small Athenian force, under the command of General Eucles.

Knowing that his force was not enough to defend the city, the Athenian general requested reinforcements, unfortunately for Athens, the reinforcements under the command of Thucydides(the well-known Greek historian) didn’t arrive in time.

Amphipolis quickly fall into the hands of the Spartans, after Brasidas promised generous terms to the people of the city.

The capture of the strategic city of Amphipolis resulted in an armistice between Sparta and Athens which ended in the year 422 B.C.

In the same year, Cleon, the leader of the pro-war faction in Athens, gathers an important expeditionary force and attempts to recapture Amphipolis.

Anticipating the danger represented by the Athenian invasion, Brasidas quickly mobilized his forces and counter-attacked.

During the battle, both Brasidas and Cleon lost their lives. Amphipolis would remain in Spartan hands.

This battle had a significant impact on the entire course of the war because, during the fight, the most important leaders of the pro-war factions(Brasidas and Cleon) from both Athens and Sparta lost their lives.

As a result, the power vacuum which appeared soon in both cities was exploited by the pro-peace factions, this would ultimately lead to the signing of what is known today as the Peace of Nicias in the year 421 BC.

Consequences:

-Amphipolis remains in Spartan hands

-last major victory for Brasidas

-Athens fails to recover the military initiative

-lost of the Pro-war leaders from both factions facilitates the start of peace talks

-the signing of the Peace of Nicias.

XI. Siege of Melos (416 BC)

Opposing forces: Athenians vs Melians

Athenians:

Commanders: Cleomedes and Tisias

Estimated strength: around 3.400 troops in the initial phase of the siege + reinforcements later

Melians:

Commanders: unknown

Estimated strength: unknown

Causes:

– the refusal of the Meliams to surrender to Athens

-Athens ambitions to gain a strategic location in the Aegean Sea.

Through the size of the forces involved, the Siege of Melos could be easily considered a minor chapter of the Peloponnesian War.

The outcome of the siege is well known, the Athenians captured the cities and sold all the male population into slavery.

It is hard to say, if the capture of Melos served the Athenian purpose, to prevent any further uprising in other city-states of the Delian League.

What is really important about this battle is represented by Thucydides’ “Melian Dialogue” which serves as one of the important lessons for the modern political realism school of thought.

Basically in the Melian Dialogue, the Athenians argue that the use of force is justified, while the Melians attempt to counter the Athenians by using moral values.

XII. Sicilian Expedition(415-413 BC)

Opposing forces: Athenians vs Spartans

Athenians

Commanders: Nicias, Lamachus, Alcibiades(would switch sides), Demosthenes

Estimated strength: between 25-40.000 troops in total

Spartans

Commanders: Gylippus and Hermocrates

Estimated strength:

Summary

If you ever wonder why Athens lost the war against Sparta in the year 404.BC, look no further than the disastrous Sicilian Expedition(415-413).

Just think in perspective, in the middle of the Peloponnesian War, the most important for Athens was to keep the Spartans and their allies in check in mainland Greece.

Suddenly, someone comes up with a grand plan.

Let’s conquer the rich city of Syracuse , then if successful other major Greek colonies in Sicily.

The idea was that the riches acquired during this expedition could fuel the Athenian war effort.

Unfortunately for the Athenians, nothing worked accordingly to the plan.

The citizens of Syracuse had proven to be fierce defenders.

At the same time, when the Spartans and Corinthians heard about the Athenian siege of Syracuse, they sent important reinforcements.

What is more interesting, these reinforcements got past the Athenian naval blockade of Syracuse (quite an effective blockade).

After almost 2 years of siege, disease, fighting, and exhaustion, the remaining Athenian forces decide to abandon the siege and retreat.

XIII. Battle of Aegospotami(405 BC)

Opposing forces: Athenians vs Spartans

Athenians

Commanders: Conon, Philocles and Adeimantus

Estimated strength: 180 ships and 36.000 troops

Spartans

Commanders: Lysander

Estimated strength:170 ships

Summary.

It is the year 405, miraculously after the disastrous expedition against the city of Syracuse, Athens manages to regroup and recover some of the lost ground.

The Athenian recovery would not last for long, Lysander, the famous Spartan admiral with strong connections to Persia, was about to make the decisive move of the war.

Having received finances from the Persians, Lysander rebuilds the Spartan fleet.

At the head of a 170-ship-strong fleet, Lysander sets sail to Hellespont and occupies the strategically important city of Lampsacus.

His main objectives were to cut the Athenian grain supply routes and capture pro-Athenian cities.

Lysander’s military campaign quickly drew the attention of the Athenian fleet commanders.

The Athenian admiral Conon, knew very well that the fate of the war itself was at stake, so he along with other commanders assembled a fleet of approximately 170 ships.

The 2 fleets would meet near the town of Aegospotami on the Dardanelles.

There are 2 accounts of the battle(Diodorus of Siculus and Xenophon), which are in conflict, so the exact chain of events is not very accurate.

Both historians, though they describe different events of the Battle, tend to agree that the Athenians were caught unprepared by Lysander.

By winning the Battle of Aegospotami, Lysander effectively knocked-out Athens and its power once and for all.

Consequences:

-the destruction of the Athenian fleet

-Athens lose the precious grain supply routes and contact with its colonies

-the beginning of the Siege of Athens

-the end of the Athenian hegemony over Greece

-the surrender of Athens and the ending of the Peloponnesian war

-the beginning of the Spartan hegemony over mainland Greece

-the dismantling of the Delian League.

XIV. Battle of Tegyra (375 BC)

Opposing forces: Boeotians vs Spartans

Boeotians

Commanders: Pelopidas

Estimated strength: 500 troops in total(300 infantry and 200 cavalary)

Spartans:

Commanders: Theopompus and Gorgoleon

Estimated strength: between 1000-1800 troops.

Causes:

Pelopidas ambition to liberate the town of Orchomenos which was still under the control of the Spartans.

Summary

Despite the small forces involved in this battle, 500 Boeotians vs 1000 Spartans; the Battle of Tegyra has more than a symbolic value.

The victory of the 300 Theban Sacred Company and 200 cavalry units against a Spartan force at least 2 times bigger proves one important fact: the Spartan invincibility on the battlefield was just a myth.

Pelopidas according to Plutarch, Pelopidas had 500 men(300 infantry soldiers and 200 horsemen).

Diodorus Sikeliotis speaks of “500 elites”. As for the Spartans, Diodorus states that they were twice as many as the Thebans, while Plutarch states that two Spartan mores (a battalion-level unit with a usual strength of 500-600 men) took part in the battle.

The Battle of Tegyra helped boost the morale of the army of the now-revived Boeotian League, this symbolic victory definitely had an impact on the final outcome of another major battle, the Battle of Leuctra(371 BC).

Beyond the human and material losses, what was mortally wounded during this battle, was the Spartan prestige.

It was the first time since a Spartan force outnumbered their enemies, and was so decisively defeated.

Consequences:

-the Boeotians had proven for the first time that they could defeat the Spartans in open battle.

-The myth of Spartan invincibility was effectively broken into pieces

-a symbolic victory which boosted the morale of the Boeotians

-the Battle of Tegyra prepared the ground for another major encounter, the Battle of Leuctra.

XV. Battle of Leuctra (371 BC)

Opposing forces: Boeotians vs Spartans

Boeotians

Commanders: Epaminondas and Pelopidas

Estimated strength: around 6-7000 hoplites, possibly supported by by 1.500 cavalry units

Spartans:

Commanders: Cleombrotus I, king of Sparta

Estimated strength: around 11-12.000 troops(hoplites and cavalary)

Causes

-Spartan interference in internal Theban affairs

-Thebans ambition to gain independence and reestablish the Beotian League

-Spartan attempt to maintain their hegemony over Greece

Summary

Another major battle that deserves more attention because it represents another turning point in the balance of power between the ancient Greek city-states.

Spartan supremacy over mainland Greece, which was hardly acquired after the costly Peloponnesian war(431-404 BC), was quickly crushed by a brilliant military commander on the battlefield of Leuctra in 371.

Leuctra marks both the end of Spartan dominance over Greece and the rise of the Boeotian League as a regional power.

Consequences:

-Spartan hegemony over Greece is over

-rise of the Boeotian League to the status of regional power, with aspirations to become the new Hegemon of Greece.

-invasion of the Peloponnese Peninsula by the Thebans and their allies

-Epaminondas and his army was at a point a few miles close to Sparta itself

-the liberation of the helots

-the creation of the “Arcadian League” with the goal of keeping the Spartans in check

XVI. Battle of Mantinea (362 BC)

Opposing forces: Spartans and their allies(Athens, Elis, and Mantineia) versus The Beotian League, Argos, and Arcadia.

Pro-Spartan coalition

Commanders: Agesilaus II, Podares of Mantinea, and Cephisodorus of Marathon

Estimated strength: around 22.000 troops, from this total 2.000 were cavalry units

Boeotians

Commanders: Epaminondas

Estimated strength: between 25-30.000 troops(hoplites and cavalry units)

Causes:

-Sparta’s humiliating defeat at the Battle of Leuctra(371 BC)

-Epaminondas ambition to establish a new hegemony over Greece

-Sparta’s attempt to recover the lost hegemony over Greece

-Mantinea’s rebellion against Thebes

Summary

After the humiliating defeat suffered during the Battle of Leuctra(371), Spartan’s hegemony over Greece started to break into pieces.

Epaminondas at the same time wanted to replace this hegemony with the Theban one. As a result, he established the “Arcadian League” with some of the cities from the Peloponnese peninsula which were traditional enemies of Sparta.

The goal was to contain the Spartan power in the Peloponnese peninsula, while also expanding the influence of Thebes.

The Theban plan would soon backfire, because Mantineia, one of the initial members of the Arcadian league, decides to switch sides and join the Spartans.

Desperate to reestablish control, Epaminondas gathers an army, estimated at around 25-30.000 troops, and marches into Peloponnese to deal with this new threat.

At the same time, the Spartans were supported by the Athenians who don’t want to see the Thebans obtain total control over Greece. The fear of the Athenians was that their city would be next.

With the support of the Athenians and their allies, the Spartans were able to field an army of 20.000 troops and around 2.000 cavalry units.

The decisive clash would take place on July 04, 362 BC near the city of Mantineia.

After using the same hoplite formation tactic as in the Battle of Leuctra, Epaminondas prevails on the battlefield, but during the fog of the battle, the Theban leader was mortally wounded.

At the same time, his designated successors to the leadership of the Beotian League also lost their lives.

As a result, the Thebans won the victory on the battlefield, but they suddenly found themselves in a political crisis and could not exploit the victory.

The Spartans at the same time having suffered heavy losses were not able to take advantage of the power vacuum in the Theban camp.

Since both alliances were weakened as a consequence of the battle of Mantineia, many historians agree that the winner is the one who didn’t participate in the battle.

The real victor of this battle is the Kingdom of Macedon because with both Sparta and Thebes now exhausted because of the constant fighting, there was simply no Greek city-state capable of opposing the growing power of Macedon.

Consequences:

-the death of Epaminondas, a great Theban statesman and general

-inconclusive outcome

-power vacuum followed by the political decline for the Thebans

-huge losses for the Spartans meant that they were unable to recover

-the Battle prepared the ground for the rise of the Kingdom of Macedon.

XVII. Battle of Chaeronea (338 BC)

Opposing forces: Macedonians vs a broad coalition of Greek-city states

Macedonians:

Commanders: Philip II and Prince Alexander(not yet the Great)

Estimated strength: a total of 32.000 troops(30.000 infantry and 2.000 cavalry)

Greek city-states

Commanders: Theagenes of Thebes, Chares of Athens, Lysicles

Estimated strength: around 35.000 troops(infantry and cavalry)

Causes:

The desire of the Greek-City states to oppose the influence of the Macedonian King Philip II.

Summary.

Before the year 359 BC, Macedonia was a second-rate kingdom, with little to no power of influence, often at the mercy of its neighbors.

All of these will change with the rise of Philip II to the throne in the year 359 BC.

Through a series of military and political reforms, Philip radically transformed the Kingdom of Macedon, from an obscure kingdom to a power that would be capable of later challenging the Persians.

Before he could challenge the Persians, Philip like Alexander later, realized that the Greek city-states had to be subdued, so he can make sure that his homefront is secured.

Philip’s greatest rival, who energetically campaigned against his attempts to unite Greece, was the Athenian orator Demosthenes.

Known for his high political skills, Demosthenes has spent most of his life, trying to build and consolidate anti-Macedonian coalitions.

Both Philip and Demosthenes knew very well, that a decisive battle for the future of Ancient Greek city-states was inevitable.

The pretext for this battle would be given by a sacrilegious act committed by the citizens of Amphissa, which outraged the Athenians.

Because Philip II had a seat in the Amphitrionic League, he had the right to intervene in favor of Amphissa, his intervention would anger both Athens and Thebes and start the later chain of events.

Philip II marched with a 32.000 strong army in the year 338 BC, and on August 2 was ready for the decisive fight.

Phillip’s army had the advantage given by experienced troops and higher quality equipment, while the coalition army of Athens and Thebes lacked military experience.

Philip’s right flank, with him personally in command would attack the Athenian right flank.

The left flank of the Macedonian Army was in charge of the 17-year-old prince Alexander, Philip’s son.

The battle started with the attack of Philip’s right flank against the Athenian flank.

From here, it is not exactly known whether Philip himself ordered a retreat to lure the Athenians out of their positions or if it was something spontaneously, what we know for certain is that the Athenians left their positions and advanced against the Macedonians.

This means that the Athenian formations were not isolated from the rest of the coalition army, significantly decreasing their cohesion in battle.

This tactical error of the Athenians would be fully exploited by Alexander who ordered the charge of the Macedonian troops from the Center and Left flank against the now-isolated Theban and other Greek city-states troops.

Alexander’s decisive attack represents the major turning point in the battle. The Center and right flank(with the exception of the Sacred Band) were quickly routed.

There was no doubt from this point who won the battle.

According to ancient sources, Macedonian casualties were minimal, around 140 troops(hard to believe figure), while from the Coalition forces, 2000 soldiers had lost their lives, and a few other thousand troops were captured.

Without the major Macedonian victory at Chaeronea, Alexander’s Great Campaign against Persia would not have been possible.

The consequences of this Battle cannot be denied or underestimated: Most of the Greek city-states, with the exception of Sparta, were now firmly under Macedonian influence.

After the victory at Chaeronea, Macedon effectively became the Hegemon(dominating power) over Greece and there was no other force capable to challenge this reality.

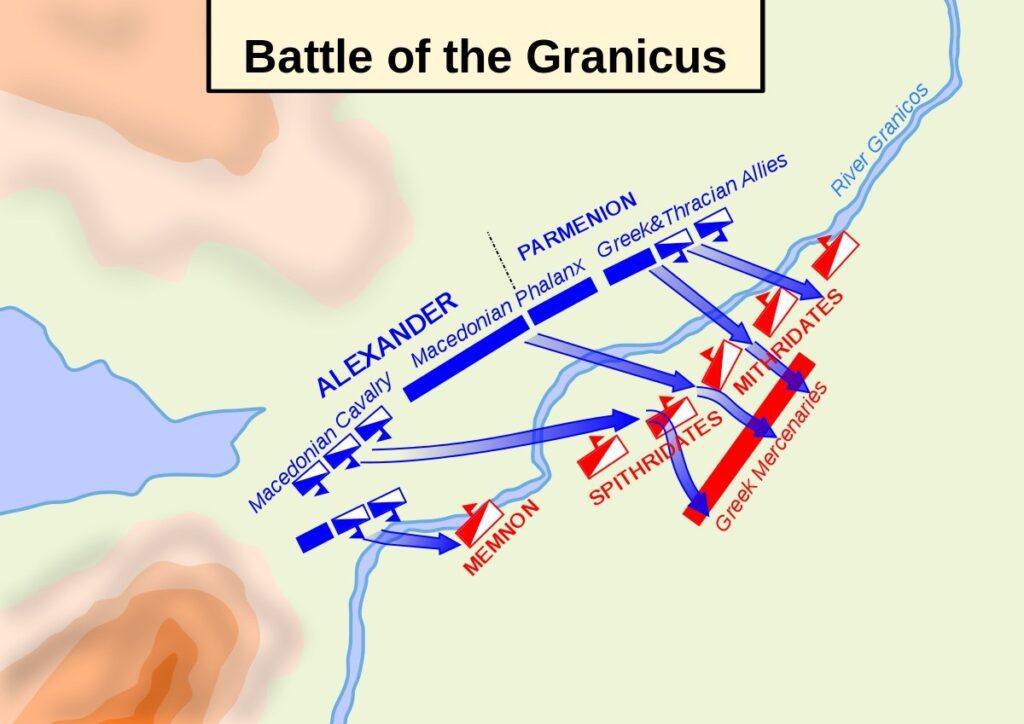

XVIII. Battle of Granicus(334 BC)

Opposing forces: Macedonians versus Persians supported by Greek mercenaries

Macedonians:

Commanders: Alexander the Great, Parmenion, Craterus, Philotas, and others…

Estimated strength: between 35-47.000 total troops(hoplites, companion cavalary and other units)

Persians

Commanders: Memnon of Rhodes, Arsites, Spithridates, and others.

Estimated strength: around 40.000 troops, mostly light infantry and a contingent of Greek mercenaries.

Summary

It is the spring of year 334 BC, Alexander with his combined Macedonian and Greek armies crosses the Hellespont into Anatolia, his official goal was to liberate the Ioanian Greek city-states from the oppressive rule of the Persians.

Ancient sources note that Alexander only brought with his army enough supplies and finances for just 1 month. A risky gamble.

So to quickly replenish the money and supplies, Alexander desperately needs a victory against the Persians so he can solve these issues.

The Persians, despite the wise advice offered by the Greek mercenary commander, Memnon of Rhodes, decide to meet Alexander and his army on the battlefield.

The chosen place will be the Granicus river.

The location wasn’t very advantageous for the Persians, because most of their army was made up of cavalry, so defending a river was not the best option for cavalry maneuvers.

Alexander and his army arrive in the afternoon near the river, sometime in May 334 BC.

Against Parmenion’s advice to camp and attack the next day, Alexander like on many other occasions, orders an immediate attack on the Persian positions.

Alexander commanded the companion cavalry on the right flank, while Parmenion led the cavalry charge from the left flank.

The center of the Macedonian army was made up of the bulk of the infantry forces.

Alexander charged first with his cavalry against the center of the Persian army.

The Macedonian quickly crosses the river, before the arrival of the phalanx, and engages the Persians in a fierce fight.

During this phase of the battle, Alexander was close to being killed several times, but each time, he manages to evade any fatal blow.

After a time, the Macedonian and Greek phalanx successfully crosses the river and the situation turns in favor of the Macedonians who were now in control of the riverbank.

The Persians, after suffering losses and with most of their commander’s death, decide to leave the battlefield.

The last troops of the Persian army who offered the last stand were the Greek mercenaries, but their resistance only delayed the advance of Alexander’s army.

Because most of the Persian army retreated, their casualties were low, somewhere around 1000-2500 deaths.

Not surprisingly, the Greek mercenary losses were higher and the ones who surrendered were sold into slavery.

The Battle of Granicus thus enters in history as Alexander’s first victory against the mighty Achaemenid Empire.

The path towards the interior of the Persian Empire was now open.

After the defeat suffered at Granicus, King Darius III realizes that he must personally deal with the threat represented by the young Macedonian ruler.

XIX. Battle of Issus (333 B.C)

Opposing forces: Macedonians vs Persians

Macedonians

Commanders: Alexander the Great

Estimated strength: around 37.000 troops

Persians:

Commanders: Darius III and other satraps.

Estimated strength: according to ancient sources between 250-600.000 troops, modern historians agree on between 50-60.000 troops.

Causes:

-Alexander the Great’s ambition to destroy the Persian Empire

-Darius III’s attempt to block the Macedonian army’s advance.

Summary.

After the great victory at the Battle of Granicus, Alexander the Great’s army quickly conquers Asia Minor and marches into Syria.

The Persian ruler, King Darius III, assembles a significant army and tries to block the Macedonian army’s advance.

Ancient sources greatly exaggerate the size of the Persian army(600.000 infantry troops and 100.000 horsemen). Modern historians agree that a plausible number would be of about 100.000 Persian troops in total.

The Persian force would be led for the first time by King Darius himself, despite the contrary suggestions from his advisors.

The decisive Battle would take place in November 333 BC, near the city of Issus in Cilicia.

Alexander the Great’s victory at Issus paves the way for the quick conquest of Phoenicia, Palestine, and Egypt.

The victory at Issus would cement Alexander’s reputation as a great military leader, while Darius III suffers a prestige and moral defeat.

It was the first time in history when the Persian army under the personal command of Darius III was so decisively defeated.

With the Eastern Mediterranean regions secured, Alexander was then able to turn his attention toward the heart of the Persian Empire and crush the mighty Persian army again at the Battle of Gaugamela.

XX. Battle of Megalopolis (331 BC)

Opposing forces: Spartans vs Macedonians

Spartans

Commanders: Agis III

Estimated strength: around 20.000 troops

Macedonians:

Commanders: Antipater

Estimated strength: 40.000 troops

Causes:

Spartan ambitions to overthrow the Macedonian rule over the Greek city-states.

Summary

The Battle of Megalopolis fought near the Peloponnesian city with the same name, represents the final stand of the Spartans against the Macedonian rule and at the same time their last attempt to regain influence and power over the Greek mainland.

The Spartan King Agis III, knowing that Alexander the Great was away with the bulk of his army, waging war against the Persians in Asia, took advantage of this situation and carefully planned one last attempt to regain power for Sparta.

With the help of money from the Persians and a mercenary force of 8000 soldiers, Agis III first captured Crete, then liberated the Peloponnesian Peninsula of any Macedonian influence.

Macedonian commander, Antipater, who was left by Alexander in charge of Greece and Macedonia, was initially at war against barbarian tribes in Northern Greece and Thrace.

Antipater quickly concluded a peace treaty with the barbarians and with financial support from Alexander, recruited an army of Macedonians and mercenaries of around 40.000 troops, double the size of the enemy Spartan army.

The Macedonian leader marched with his new army through the Isthmus of Corinth and recaptured the cities of Corinth and Argos.

Agis had no option left but to list the siege of Megalopolis.

XXI. Battle of Gaugamela(331 BC)

Opposing forces: Macedonians vs Persians

Macedonians

Commanders: Alexander the Great

Estimated strength: around 47.000 troops

Persians

Commanders: Darius III, Bessus and Mazaeus.

Estimated strength: according to modern estimates the agreed statistics range from 50.000 to a maximum of 120.000 troops.

Ancient sources speak about 250.000 to even 1 million troops.

Causes:

-Alexander’s ambition to conquer the whole Persian Empire

-Darius’ attempt to stop the Macedonian advance in a decisive battle.

Summary:

If Granicus and Issus represent the first and second dents in the prestige and might of the Persian Empire, the Battle of Gaugamela is the mortal wound, one from which Darius III and his Empire would never recover.

Gaugamela represents Darius III’s last stand against the mighty Macedonian army advance.

Despite having this time favorable terrain for maneuvering, the Persian army failed to break the ranks of Alexander’s army.

During the decisive battle, Alexander repeated the same strategy used during the Battle of Issus, 2 years previously.

When Alexander observed that Darius’ center became fragile, and the position of the Persian ruler was vulnerable, Alexander himself at the front of his Companion cavalry marched against them.

Darius, exactly like during the Battle of Issus, refused to fight till the end and flees the battlefield.

Alexander proved once again how personal leadership and bravery can make a difference when the numbers were not on his side.

After Gaugamela, Darius III retreats further East into the mountains with the remaining loyal troops.

Babylon, Persepolis, and Susa have fallen under Macedonian rule.

With the sacking of Persepolis, Alexander completed the wish for revenge of the Greeks caused by the invasions of Darius I and Xerxes.

Consequences:

-failure of Darius III to stop Alexanders’ advance into the Persian Empire

-the fall of the major Persian centers(Babylon, Susa, Persepolis) into Macedonian/Greek hands

-the Battle of Gaugamela will ultimately lead to the fall of the Achaemenid Empire.

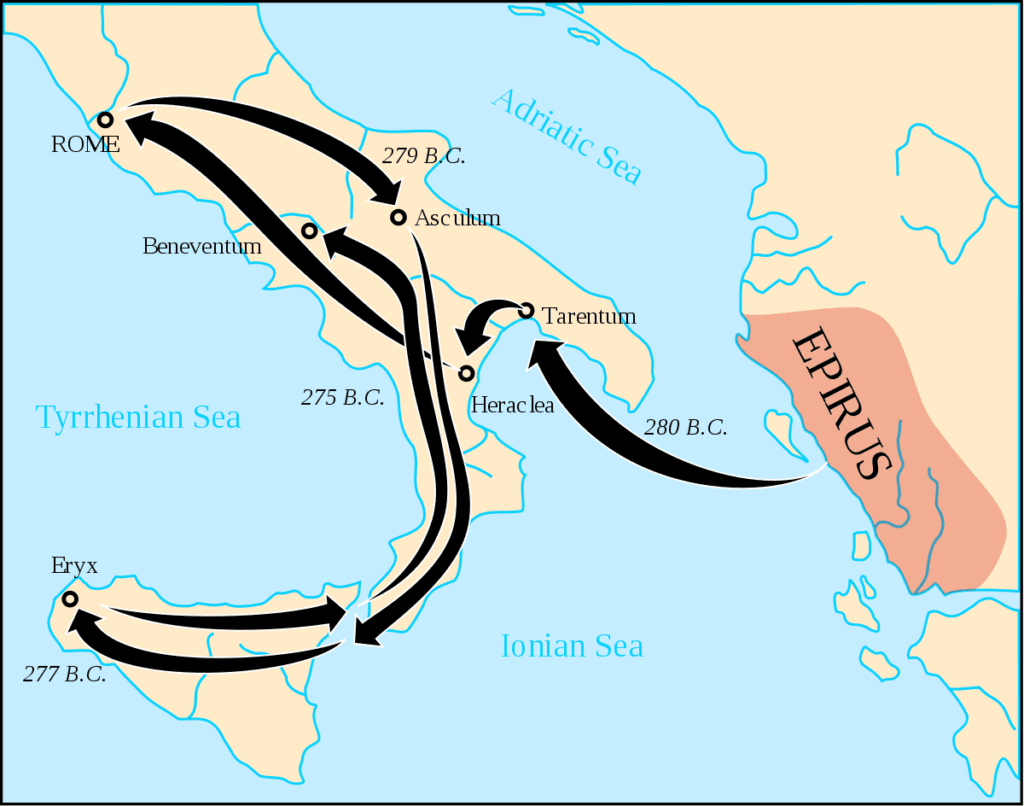

XXII. Battle of Heraclea (280 BC)

Opposing forces: Romans vs a coalition of Greek city-states

Romans

Commanders: Publius Valerius Laevinus

Estimated strength: around 45.000 troops, most of them heavy infantry, around 2000-6000 were cavalry units.

Greek city-states

Commanders: Pyrrhus of Epirus

Estimated strength: around 35.000 troops, most of them hoplites.

Also supported by a force of 20 war elephants.

Causes:

-Roman expansion in Southern Italy

-End of the Roman-Samnites war

-Tarentum’s request for military aid to King Pyrrhus

-Pyrrhus’ ambition to gain more power and influence

Summary

With the end of the Roman-Samnites wars, following the Roman victory at Sentinum(295 BC); it was obvious that the next target of Roman expansionism in Italy was the wealthy Greek colonies in Southern Italy.

One of these colonies, Tarentum(Taranto) anticipating the threat represented by the Romans, asked for external military support from the King of Epirus, Pyrrhus the Great.

Pyrrhus had a number of reasons to help the Tarentines. First, the Greek colonist helped him in the past during the conquest of the Island of Corcyra.

Secondly, the Greek military leader had his own ambitions, to gather money and a large army through military conquest so he can recover Macedon.

Pyrrhus’ well-earned victory at Heraclea came at a great cost, around 15% of the total strength of his army. Off course, he could count on additional reinforcements from Greek city-states, but it is very hard to replace experienced troops.

The victory of Pyrrhus of Epirus at Heraclea allowed the Greek leader and his army to plunder cities and villages in Etruria and Campania regions.

According to some historians, Pyrrhus with his army at the peak of his advance was only 2 days of march from Rome.

The only obstacles that prevented the Greek king from capturing Rome were the lack of siege equipment, supply issues, and new Roman reinforcements.

One more important note, the Battle of Heraclea represents the first major clash between the Roman legions and the Greek phalanx, the 2 most used military formations of Ancient times. In this first clash, the Greek phalanx prevailed.

XXIII. Battle of Asculum (279 BC)

Opposing forces: A coalition of Greek city-states vs the Romans

Greek city-states

Commander: Pyrrhus of Epirus

Estimated strength: around 40.000 troops supported by 19 war elephants

Romans

Commanders: Publius Decius Mus and Publius Sulpicius Saverrio

Estimated strength: around 40.000 troops with 300 anti-war elephants carriages.

Causes:

-Tarentum’s request for military aid against the Romans

-Roman expansion into Southern Italy which was perceived as a threat by Greek city-states.

-Pyrrhus’ dream of rebuilding the Macedonian legacy

Summary

After the defeat of the Samnites in 295 BC, the path of Roman expansion in Italy moves further South against the region controlled by important Greek city-states, especially Tarentum.

This city, anticipating the threat represented by the Romans, asked for foreign military support from the King of Epirus, Pyrrhus.

Pyrrhus had his own ambitions when he decided to help the Tarentineans. He thought that he could rebuild at least part of the Macedonian power legacy with money and troops he could obtain by conquering parts of Southern Italy and Sicily.

The result of this decision would be a series of military battles against the Romans with the same results, the troops of Pyrrhus would emerge victorious but with high losses. Thus from these battles, we now know today the expression: “Pyrrhic victory”.

The Battle of Asculum is the second battle fought on Italian soil against the Romans, by King Pyrrhus’ army and his Allies.

Records about the outcome of this battle are conflicting, Plutarch speaks about the victory of Pyrrhus, while historian Cassius Dio claims that the Romans won the day.

One thing is certain, Pyrrhus suffered great losses, that he could not afford to replace and was forced to withdraw and regroup elsewhere.

Sources and Further Reading

- Mike Roberts and Bob Bennett, Spartan Supremacy 412-371 BC, Pen&Sword Military.

- Nicholas Sekunda, The Spartan Army, Osprey Publishing; 1st edition (November 11, 1998)

- Duncan B Campbell, Spartan Warrior 735-331 BC, Osprey Publishing

- Nicholas Sekunda, Marathon 490 the First Persian Invasion of Greece, Osprey Publishing

- Murray Dahm, Leuctra 371 The Destruction of Spartan Dominance.

- Simon Elliott, Ancient Greeks at War, Warfare in the classical World from Agamemnon to Alexander, Casemate Publishers.

- John Warry, Alexander 334-323 BC Conquest of the Persian Empire, Osprey Military

- Simon & Schuster, The Battle of Salamis: The Naval Encounter that Saved Greece, and Western Civilization.

- Peter Krentz, The Battle of Marathon, Yale University Press.

- Nic Field, Syracuse 415–413 BC: Destruction of the Athenian Imperial Fleet, Osprey Publishing

- Herodotus, The Histories, Penguin Publishing Group, 2003

- Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War.

- Patrick Alan Kent, A history of the Pyrrhic War, Routledge Studies in Ancient History.

- Murray K. Dahm, Breaking the Spartans: Epaminondas, Pelopidas, and the Brief Glory of Thebes, Skyhorse Publishing Company.

- Donald Kagan, The Fall of the Athenian Empire, Cornell University Press

- Lee L. Brice, Greek Warfare: From the Battle of Marathon to the Conquests of Alexander the Great, ABC-CLIO.

- Paul Chrystal, Wars and Battles of Ancient Greece, Fonthill Media

- Owen Rees, Great Battles of the Classical Greek World, Pen and Sword.

Final impressions

We hope that this list of famous Ancient Greek battles helped you to obtain a much clearer image of the role and importance of Greek military history in the Ancient World and not only.

These Ancient Greek battles, not only save the Greek city-states and many known values of the Ancient Greek civilization. But also preserved these values for the modern world.

If you have another famous Ancient Greek battle that is worth to be mentioned, leave it in the comments and we will add it to this list after doing the necessary research.

Pingback: Battle of Tegyra(375 BC) - Breaking the myth of Spartan Invincibility - HistoryForce