The Turnip Winter of 1916/1917 (German: Steckrübenwinter) was a major food crisis during the First World War in Imperial Germany, which particularly affected the major cities. The crisis began with a blockade of the North Sea enforced by Great Britain and its allies with the primary goal of stopping the food shipments and essential supplies to Germany. The blockade ended in 1919 when supply routes were restored.

The name comes from the fact that because of the severe food shortages, the Germans were forced to eat turnips, which until then were used only as food for livestock.

The Entente’s naval blockade was considered for a long time by many historians to be primarily responsible for the catastrophic food shortages.

In recent times, more specialists consider that more likely a combination between the inefficiency of Germany’s agriculture to sustain the wartime efforts and bad economic and food management decisions are the main responsible for the crisis.

The disastrous Turnip Winter was followed by serious social unrest and major political tensions that ultimately led to the collapse of the German armies, revolution, and the downfall of the German Monarchy.

I. Historical Context.

At the beginning of WWI, Imperial Germany was forced to wage war on 2 fronts against forces with more resources than its own.

Expecting a quick victory like in 1870/71, the Germans didn’t take the necessary steps to mobilize their economy and especially their agriculture for a long conflict.

A bigger mistake, was because the Germans thought that the war would end quickly, no food reserves were created. Of course, not only the leaders of the German Reich thought that the war would be short.

Only after the failure of the Schlieffen- Plan, did state authorities at the national and regional level try to intervene in the production and distribution of food.

II. Turnip Winter – Most important causes for the food shortages

The main causes of the food shortages during the Turnip Winter need to be separated into 2 major chapters: causes related to the performance of Germany’s agricultural sector before WWI, and causes directly related to the main events of the war.

A) German Agriculture before WWI

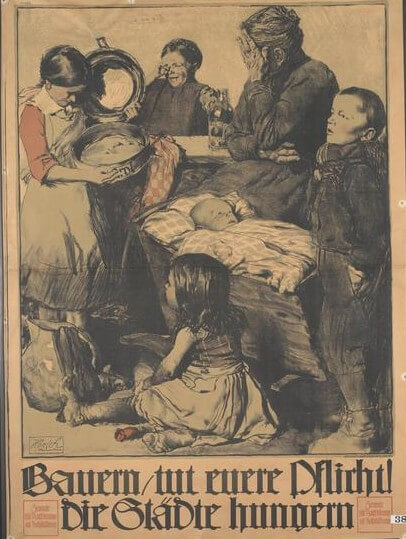

Source: https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/13556

Between the years 1870-1913, the economy of Imperial Germany was growing at an accelerated pace.

Fueled by industrialization, in 1913 Germany became the second-largest producer of industrial goods in the World.

One of the main consequences of industrialization is that the share of agriculture in the national GDP declined from 37% in 1885 to 25% before WWI.

The exponential growth of the German industrial sector didn’t translate into accelerated growth in agricultural production.

Between the years 1850-1913, the agricultural production of Germany rose by a modest figure of only 2% every year. Not enough to reach self-sufficiency before the start of WWI.

Imperial Germany during Bismarck and later Kaiser Wilhelm II’s rule failed to achieve autarchy in the supply of agricultural products, a mistake which would cost them the victory during WWI.

Before 1914, approximately 25% of the total food consumption came from imports.

Most of the German food imports consisted of dairy products, eggs, vegetable oils, fish, and meat.

Meat production was especially vulnerable because Germany before the war imported 6 million tons of animal fodder annually from Russia.

In 1913, Germany harvested approximately 4.655.956 tons of wheat and imported 2545.958 tons, a significant part of the imports came from Russia and the USA.

In 1913, Germany imported 210.000 tons of chemical fertilizers(most of them from Chile) to sustain the productivity of its agriculture. Because of the Allied Blockade, imports fell to 80.000 tons annually.

The ability of German agriculture to secure self-sufficiency for the rapidly growing population for a long period was simply overestimated.

B) British Naval Blockade

Before WWI, Germany attempted to challenge the British Naval Supremacy by building its navy.

At the start of WWI, though the Germans had an impressive Navy, it wasn’t powerful enough for breaking the British Naval Blockade.

German Navy strength in 1914: 17 modern dreadnoughts, 20 battleships (pre-dreadnought design), 5 battlecruisers, 25 cruisers, 10 diesel-powered U-boats, and 30 submarines powered with petrol.

British Naval strength in 1914: 18 modern dreadnoughts, 29 battleships (pre-dreadnought design), 10 battlecruisers, 20 town cruisers, 15 scout cruisers, 200 destroyers. The Royal Navy also had 150 cruisers built before 1907.

Overall, the numbers are in favor of the Royal Navy. The Germans were not able to defeat the British, but the Royal Navy and its Allies had no problems with enforcing a total economic blockade of Germany.

The Allied Blockade had immediate effects at the outbreak of the war, the entire German merchant fleet, which was vital for agricultural imports, was effectively banished from the oceans. Approximately 245 ships were captured, 1059 were confiscated in neutral ports, and 221 were trapped into the Baltic Sea.

Until 1916, the Germans were partially successful in delaying the effects of the British Blockade by intensifying the food trades with neutral countries(the Netherlands and the Scandinavian Countries).

The British didn’t stand idle and put pressure on the neutral countries to reduce their commercial relations with the Reich.

The consequences of the British naval blockade would be felt gradually, and the German civilian population would be the one to pay the high price.

The German Forces knowing the consequences of the British Blockade retaliated with an unrestricted submarine war against the British but this action backfired because it resulted in the entry of the US into the war.

The result of the US entry into WWI would be that the economic blockade was even more thought.

C) German Agriculture performance during WWI.

We already underlined how little prepared was German agriculture before the beginning of the hostilities in 1914. The important question now is: How did German agricultural production evolve during the war?

In 1914 and 1915, total agricultural output fell by 11% and respectively 15% from its 1913 production level.

In 1916, the decline was even worse: 35% from the pre-war levels.

Potato production in the German Empire fell from 52 million tons (1913) to 29 million tons (1918), and grain yield fell from 27.1 million tons (1914) to 17.3 million tons (1918).

There are many causes behind the severe decline of agricultural output in Imperial Germany during WWI.

1. Labour shortages.

Labor shortages in agriculture were caused by massive conscription of the farmers(approximately two-thirds of the total male workforce in agriculture were conscripted at the beginning of the war).

Without the skilled workforce in agriculture, productivity and efficiency gradually started to decline.

Forced laborers, prisoners of war(approximately 900.000 prisoners were used for working the land), and students were used to overcome the shortage of skilled workers in agriculture, but full compensation could not be achieved, especially since many factories had switched to armaments production and there was, therefore, a shortage of both agricultural machinery and fertilizers.

2. War mobilization.

Approximately a third of the total number of farm horses were also mobilized for the war effort.

Horses were very effective for carrying large guns, supplies.

The absence of horses affected agricultural production because they were intensively used for sowing and plowing.

3. Hindenburg Plan and the Command Economy.

When Paul von Hindenburg and Erich von Ludendorf took power in 1916, they quickly realized that for winning the war, ammunition and industrial production had to be prioritized.

Known today as the Hindenburg Plan(1916), it marked the command economy phase for the German wartime economy efforts.

By concentrating the majority of the resources into the armaments and industrial goods that were vital for the war effort, the Hindenburg Plan further worsened the labor shortages in agriculture and contributed in the long run to the overall decline in agricultural productivity.

4. Schweinemord: The Great German Pig Massacre

The best example of how ineffective the command economy and economic planners can be during wartime is represented by the Great German Pig massacre, which occurred in March/April 1915.

Because in 1914 the central government decided to freeze potato prices, German farmers thought it was much more profitable to use potatoes as fodder for pigs.

This created the impression that pigs were competing with humans for food.

In an attempt to solve both the potato and meat supply problems at the same time, the German government has signed the death warrant for 9 million pigs, out of a total of 27 million.

As you may have guessed, in the short term the meat supply was resolved, but in the long run, this decision would become one of the main causes of Turnip Winter.

Pigs were an important source of natural fertilizers and therefore had an important contribution to overall agricultural productivity.

Without knowing, the German bureaucrats had put another nail in the coffin of German agriculture.

5. Poor Weather

On top of the British Naval Blockade and the labor shortages in agriculture, the unfavorable weather of 1916 dealt a decisive blow to German agricultural production and the war effort as a whole.

At the peak of the food shortages in 1916, rainy autumn combined with a harsh winter destroyed almost 50% of all potato harvest.

The unfavorable weather of 1916 and early 1917 contributed to the severe decline in the production of potatoes, a food that was used by the Germans for the majority of the substitute products.

Pre-war German potato production was estimated at 52,000,000 tons, and in 1916-1917 it plummeted to 17,000,000.

III. Turnip Winter – analysis, chain of events and consequences

According to a study, The Food Supply of Germany during the War, the normal consumption of a person per day necessary for the proper conduct of activities is 3000 calories.

The average daily caloric requirement was set at 2000.

On the other hand, factory workers needed a daily intake of 4000-5000 calories.

According to the same study that used the Eltzbacher Commission reports as a source of information, the daily calorie intake for a German before WWI was around 3642, while for men alone it was 4335 calories.

Compared to the intake rides in the UK and France (3,800 and 3400 calories respectively), Germany was doing well in this regard.

In the spring of 1916, the official rations established by the German authorities were approximately 1985 calories per day.

Food was rationed, the so-called “war bread”, which consisted of potato flour, was introduced on large scale. Milk was diluted with water and given primarily to mothers.

In addition, there were rations of 1.5 kg of flour and 100 g of fat per week.

More and more replacement products, so-called surrogates, were introduced. Towards the end of the war, there were over 10,000 of these products, such as coffee substitutes made from grated and dried turnips/swedes.

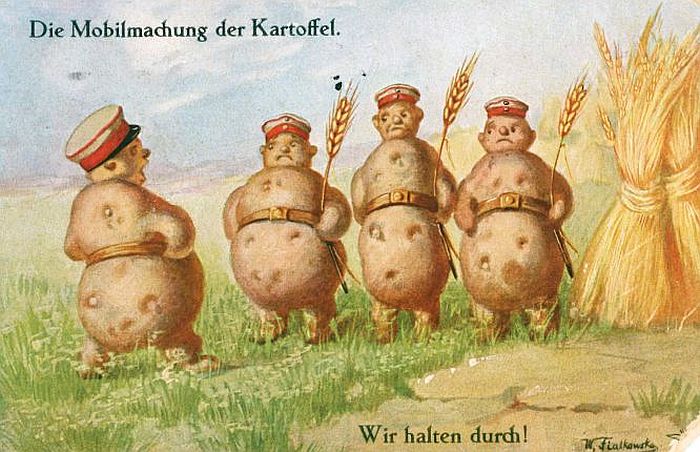

The situation finally escalated in the winter of 1916/17: bad autumn weather meant that the potato harvest, which had been the staple food until then, was halved. The turnips were used as a substitute, which until then had primarily been used to feed livestock.

Rationed swedes and turnips were given out as a substitute for the staple food. They are extremely robust, thrive in practically any weather and you hardly need artificial fertilizer for them, which was no longer available in sufficient quantities during the First World War. In addition, turnips are comparatively rich in vitamins, which was extremely important because of malnutrition. However, turnips have a rather small calorie content, which is why, despite their massive use, they were only insufficiently able to cover the calorie requirements of adults.

Leaflets and wartime cookbooks gave tips on how to make nutritious meals from turnips/swedes. In the morning, at noon, and in the evening only turnips- most Germans could no longer see them, and those who survived the war no longer wanted to eat them in the 1920s.

The average calorie intake of an adult German fell dramatically from the average of 3,000 calories per day in 1913 to less than 1000 calories per day during the Turnip Winter of 1916-1917.

The official rations reached only 1344 calories per day, of which protein was only 31 grams. And these were only official estimates, on paper, the reality could’ve been harsher.

The situation improved somewhat in the summer of 1918 when daily calorie intake was estimated at 1400. One and a half years after the start of the Turnip Winter crisis, the German authorities still failed to provide a daily minimum of 2,000 calories.

According to official estimates during this time, every average German lost between 12-25% of their body weight.

On March 17, 1916, doctor Alfred Grotejahn wrote in his diary about the consequences of malnutrition: “The population of Berlin is getting more and more Mongolian in appearance every week. The cheekbones are protruding and the defatted skin is wrinkling.”

Alonzo Taylor, an American psychologist who lived in Germany during the war wrote “The familiar obesity of the Germans has disappeared”.

The most relevant experiment that reveals the harsh conditions of these times was done by a German Nutritionist, R.O.Neumann. Between November 1916-May 1917, he attempted to live only with the official state rations. The result was that he lost a significant amount of body weight, from 76.5 kg to 57.5 kg.

Even the famous commander, Erich Ludendorff, in his memories, admitted that the food shortages were a major issue:

“In wide circles, a certain decay of bodily and mental power of resistance was to be seen … This attitude was a tremendous element of weakness … It could be eliminated to some extent by strong patriotic feeling, but in the long run could be finally defeated only by an improvement of nourishment.”

According to official estimates by the German authorities, 762,000 people have lost their lives due to hunger.

It was found that among the deaths, in most cases they lost over 30% of their body mass.

During the war years, infant mortality rose by 50 percent, twice as many mothers died as a result of childbirth as before the war. Female mortality rose by 23 percent between 1916-1917 and it reached 50% in 1918. The number of births in Berlin in 1917 was less than half what it was in 1913.

The food shortages were not only limited to the German Homefront, they also reached and affected to some degree the efficiency of the Imperial army on the battlefields. The exact degree is not yet very well known.

British intelligence reported that the German government had reduced soldiers’ rations on 13 April, substituted dried husks for coffee, and reduced the rations for horses to 25 percent of their level at the beginning of the war.

We must not ignore the fact that for the survivors, the rapid loss of such a large percentage of body mass also meant a decrease in the immune system.

As a result, the famine caused a significant decline in the immunity system of the German people, who were now more prone than ever to dangerous diseases such as tuberculosis or influenza.

A German nation with its immune system severely hit by the massive food shortages was again hit in 1918 by the outbreak of the Spanish Flu. The combination of the low immunity of the German people and the lack of any means to counter the Flu resulted in another 350.000 civilian lives lost.

Between the years 1913-1918, mortality caused by tuberculosis in towns with a population of over 15.000 inhabitants, also rose by 91%.

The resulting dissatisfaction within the population gradually led to a loss of legitimacy of the state towards its population. This was less and less interested in any victory reports from the front but was busy with the question of where to find food the next day.

In August 1916, a group of soldiers’ wives wrote to local authorities in Hamburg, their primary demands were to reach a peace agreement and quickly end of hostilities: “we want to have our husbands and sons back from the war and we don’t want to starve any more”.

The food shortage finally led to a fateful decision in early 1917: the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare in the Atlantic. A desperate attempt to cut off the supply of food and war material to the British and thus force an armistice before the situation in Germany could escalate any further. Ultimately, this campaign failed and was ultimately one of the main reasons for the United States’ entry into World War I. The German situation was thus aggravated even further. The war was lost.

At the end of the war in 1918, the Imperial statistical office estimated that 762.000 people died as a result of the food shortages during the Turnip Winter. A more realistic estimation done 10 years later provided a different figure: 424.000 civilian deaths.

But even in peacetime, the effects of the wartime food shortages didn’t disappear.

IV. CONCLUSION

The British Naval Blockade, though very effective, is not the major cause of the Turnip Winter, but more likely the bullet which triggered the chain of events that ultimately led to the major food shortages in Imperial Germany during WWI.

The combination of the poor performance of German agriculture and the wrong economic decisions of the German bureaucrats are rather responsible for the catastrophe known today as Turnip Winter.

Food shortages alone didn’t defeat the Germans in WWI but were a decisive factor in the final victory of the Entente. The Germans were ultimately defeated on the field of battle.

The use of the Naval Blockade severely affected the morale and efficiency of the German Home Front and contributed to the ultimate defeat in the field of battle.

Contrary to those Germans who believed in the ‘stab in the back theory, that the war was lost when the politicians and people at home abandoned the army just as it was winning, the German army was defeated in the field.

The German army was defeated in the field of battle, not because of the betrayal of the Home Front, but because the Home Front failed to provide adequate food and other vital resources for the war effort. The Turnip Winter is the perfect example of how important is to maintain the loyalty and the good mood of the Home Front during a war.

In the long run, the hardships caused by the Turnip Winter served as a lesson for the Nazis about how important it is to achieve self-sufficiency in agriculture, before going to another war.

V. SOURCES:

Books and articles.

1. Avner Offer, The First World War – An Agrarian Interpretation, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1989.

2. Alexander Watson, Ring of Steel – Germany and Austria-Hungary in World War I, Basic Books, New York, 2014.

3. Eric W.Osborne, Britain’s Economic Blockade of Germany 1914-1919, Frank Cass, London, New York, 2004.

4. Starling, Ernest H. “The Food Supply of Germany During the War.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 83, no. 2 (1920): 225–54. https://doi.org/10.2307/2341079.

5. Dietrich Orlow, A History of Modern Germany, 1871 to Present, VIII Edition, Routledge, New York, and London.

Websites

- https://www.dhm.de/lemo/kapitel/erster-weltkrieg/alltagsleben/lebensmittelversorgung.html

- https://www.welt.de/geschichte/article124743724/Wie-der-Steckruebenwinter-zum-Trauma-wurde.html

- https://blog.woodpeckerlearning.com/de/der-steckruebenwinter-191617/

- https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/naval_blockade_of_germany

- https://www.dhm.de/lemo/kapitel/erster-weltkrieg/alltagsleben/kohlruebenwinter-191617.html

- https://spartacus-educational.com/FWWnavy.htm

- https://spartacus-educational.com/FWWgermanN.htm